Three Lessons Grief Taught Me

I'm not mining my past to say "Woe is me," but looking back can help me understand my mental health disorders.

I hope I die before I get old

“My Generation,” The Who

TLDR: Grief sucks, especially if you fight depression, but grief can also be a wonderful teacher.

Snowy was my first camp counselor in 1984 and over the years, as a six-year age difference seemed to matter less and less, we became friends. We were camp friends; if you loved spending summers at a camp growing up, you know exactly what that means. If you didn’t, I can’t explain.

Snowy was a delightful music snob who forced everyone he met to listen to The Who. He was a gifted photographer — you can still buy his photo of Gillette Stadium during the infamous Snow Bowl of 2002 in the Patriots Pro Shop. If you were lucky enough to be his friend, he had your back: Snowy was front and center at my book release party in 2007 and came to take photos when I won a cooking contest in 2010.

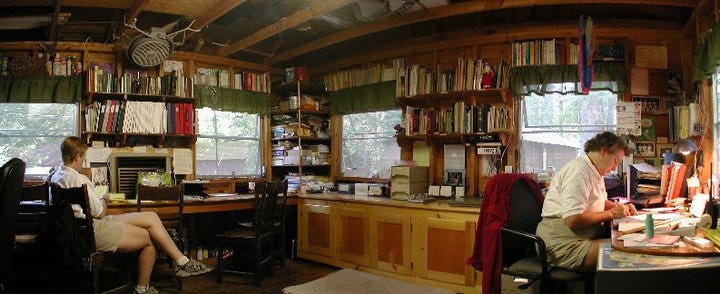

Peter Snow photo.

Any time I hung out with him was either gut-busting funny or interesting, and usually both. In October 1996 I had lunch with him when he decided —on a whim — he was going to rent a seaplane — not someday, but that afternoon. He had a new camera and wanted to take aerial photos of our island-based camp (as someone who had a fear of flying at the time, I was relieved when they said they had stopped seaplane tours over Lake Winnipesaukee for the season).

He was single despite a smile that melted hearts. He was funny as hell and great with kids. He put the top down when he gave you a ride in his new Ford Mustang in the middle of winter. He was the guy who would cook a late-night feast after hours of drinking — often with racks of ribs that had been waiting to be reheated in a cooler in his car. He had a huge heart and made my life brighter, happier, better.

And, in August 2019, he was dying.

Grief Is Brutal. Grief Is Normal. Let Us Thank It For Its Lessons

Grief is not the same thing as depression. Grief is not fun, but it is normal — as central to the human condition as joy and sorrow. It can often feel like you’re waiting for grief to run its course like a bad cold, but it is a healing process that works better with your participation. It is not about forgetting what you’ve lost or “getting over it.” Although it may take longer to fully adjust to the new reality, most people pass through grief within one to three years, with or without therapy. Beyond that, a person may be suffering from prolonged grief disorder, a diagnosis included with some controversy in the most recent edition of the DSM.

Everyone experiences grief differently, but common symptoms include apathy, anger, sadness, and regret. Grief can overwork your nervous system and cause fatigue, headaches, insomnia, and other physical symptoms.

Sounds a lot like depression’s symptoms.

Peter Snow photo.

Consider depressive apathy or depressive hopelessness that can make simple tasks seem overwhelming, then double it. A lot of people with depression, including me, are prone to insomnia. I’m much more prone to insomnia after the loss of a loved one, when I actually have something worth fretting about all night.

In addition to death, breaking up, losing a job, missed chances, lost youth, and fertility issues can cause grief. Aside from the insomnia, I thought I handled the grief surrounding those things when they popped into my life "normally," as defined by the mental health field.

Then Snowy died.

It feels disrespectful to say, but I let other parts of my life get in the way of properly grieving Snowy. Earlier that summer, Kate and I lost a pregnancy at six months. The year before, my mom and Kate’s father died within six months of each other. Then a few months after he died, that whole pandemic thing happened.

I'm not mining my past to say "Woe is me" on Fun With Bipolar, but looking back can help me understand my mental health disorders. Awareness helps me avoid the problems that riddled my life before my bipolar diagnosis. Turns out, grief can be a pretty good teacher.

Grief’s first lesson: For a long time, I’ve been beating myself up about not properly grieving Snowy’s death. My tendency towards negative self-talk had me telling myself I was a bad friend. What kind of insensitive jerk takes his three-year-old daughter to an amusement park the day before his friend’s memorial service? I was being selfish for not grieving him “like a normal person” — as if grief was a checklist of tasks to be completed on a schedule.

My therapist Renee’s mantra is “feelings are not facts.” She’s had it written on a whiteboard facing patients in her office since I started seeing her a year ago, and a lot of my work is breaking down feelings to find the facts behind them. I work back from the “I'm a bad friend” and counter it with facts: Grief is for the living, not the dead, and healthy grieving is important. It’s also a fact people grieve in different ways. I make a conscious effort to respect and not judge how people grieve. I support them however I can.

Another fact: I make a conscious effort to respect and not judge how people grieve, except when it comes to me.

I’m working on it.

Friends, how many of us have them? For real, I mean.

Snowy was always one of my “like no time has passed when we get together” friends, but after my wedding in 2013, I only saw him a couple of more times before I went to Melrose-Wakefield Hospital for one last visit a few days before he died.

Snowy had been drinking quietly, heavily, and alone during those “like no time has passed” stretches. There’s a lot of guilt tied up around his death. Not just with me, but a lot of our camp friends. And a lot of friends were initially angry during the grieving process: Snowy could have called any one of dozens of people for help.

But any one of us could have called him to see if he needed help.

I wanted to be angry at him for the same reasons, but didn’t have the right. I hid pain with heavy drinking for 20+ years. I don’t judge how people grieve and know that anger is a natural part of the grieving process. Maybe I would’ve had a smoother grieving process if I had given into it in the first few days after he died.

Peter Snow photo.

It was a boys’ camp, so most of the lifelong friendships I built over the my 13 summers were with other boys/men. Men who were boys in the ‘70s and ‘80s, men who were taught to cram emotions into the deep dark corners of the soul and never talk about them. People of a certain age remember the misogynistic mantras:

“Man up.”

“Don’t be gay.”

“Shut up and drink.

“Pussy.”

In my experience, male friendships tend to be built around experiences: golf, sporting events, concerts, video games, and whatever else floats your boat. Female relationships — again, anecdotally and in my experience — are primarily built on emotional connections. Women get together to have the experiences, but the meat of those experiences is connecting. Think of book clubs, where, as the cliche goes, the real point is to get together, drink wine, talk about life, and occasionally make a passing reference to that month’s read.

There’s scholarship showing women maintain and often strengthen bonds throughout their lives, while men statistically have fewer close friendships as they age. Of all the components of my life, the shared experience of camp was where it was easiest for me to make emotional connections with other guys. But when the summer ended and the shared experience was over, we didn’t have the skills to keep building those bonds.

Grief’s second lesson: Experience-based friendships are about forgetting your problems for a while. Emotional-based friendships are about having support to work through those problems.

Don’t fool yourself: You need both.

And whether you’re a man or a woman, making those emotional connections seems even harder now. Before the internet, I’d trade letters throughout the winter with my overseas camp friends. I checked in with stateside friends by phone. We’d get together regularly in the off-season and the first few years after we left camp. The experiences happened face-to-face in real time. But after those few years, the visits got further and further apart and the experiences eventually fizzled out.

I grieve the loss of those times. Some of it is just everyone getting older and spending more time with kids, mortgages, and other miscellaneous adult stuff. But I think a lot of it is social media.

The handwritten letters and phone calls became emails. Then they became clicking “like.” We see the smiling photos, the fancy dinners, and the happy vacations with kids who grow with each update. We subconsciously assume their lives are grand — to the extent there’s a correlation between envy-induced anxiety and the rise of Facebook. We make promises in DMs to get together soon, but soon melts into years, and the years melt into decades.

Grief Stems From Friendship, Friendship Eases Grief

In the days after Snowy died, we posted tributes and funny photos on social media. A memorial service was planned for camp in September, a beautiful time of year to be on Bear Island and the perfect place to remember someone who loved camp more than anything else.

Privately, however, we were reconnecting in a behind-the-scenes email chain. It was an emotional postmortem of what went wrong — not with Snowy but with the deterioration of the bond. Any one of us would drop whatever we were doing if anyone else on that chain was in trouble.

The question was whether any of us would reach out when we were in trouble.

Grief’s third lesson: It’s okay to ask for help.

I don’t know whether it’s a personality quirk or another fun layer of my mental illnesses, but I have hated asking for help for as long as I can remember. It comes off as trying to be independent, but it has nothing to do with that. It’s not wanting to be a burden. It’s wanting to hide and cover myself up like a bruise.

I’ve moved without help more times than I can remember, even abandoning furniture because I didn’t dare bother someone by asking for help. I’ve refused rides because I was five minutes out of the way for the driver. I can’t cook — something I love to do — with other people because I end up trying to do everything. After dinner, I do all the cleaning up because it seems unfair to make other people do it.

(The hilarious part is I make a horrible roommate; bipolar disorder ruins a good meal).

I’m a long way from mastering how to ask for help, but over the winter, as I started to make a plan to deal with my newly-diagnosed bipolar, I knew I needed friends. It’s too much to put it all on my family. I’ve been trying to reach out more, but it’s hard. I haven’t said much about my anxiety, but there’s a lot of it. And a lot of it, I’m learning, is social anxiety.

I’m trying, but since promising myself to reconnect with friends eight months ago, I’ve canceled more “let’s get caught up” lunches with lame excuses than I’ve actually gone to. COVID had been such great cover, but now I have to resort to outright lying: an unexpected meeting, car trouble, and kids who always seem to get sick at the most convenient time.

So we used the email chain to make promises that anyone of us could reach out to any of the others at any time. So far I haven’t reached out to anyone and no one has reached out to me.

And that worries me. Soon is melting into years. Years are melting into decades.

And it worries me because everyone’s life is full of the kinds of trouble that will ruin you if you don’t have a good support system in place. As I write each of these essays, I keep it front and center in my mind that everyone reading has problems worse than mine: I’ll take bipolar over cancer, divorce, the loss of a child, getting fired, and so many other ways life gets screwed up. You should click “unsubscribe” as soon as I forget that and start making “Fun With Bipolar” a sympathy play.

But examining the past — constructively and rationally — has been helpful for me, and I hope it’s been helpful for readers. I’m working on a follow-up essay on how I’m trying to resolve my grief and what’s helping and not helping me adjust to adding life’s normal roadblocks to bipolar diagnosis.

(Did anyone actually read this far? If you did, thanks!)

This is an informative, touching article on how you deal with grief and balance that and bipolar. Snowy's photos bring the viewer right into the moment. Letter writing is a lost art. You reminded me of camp days from many decades past.

Thanks for sharing this David. I found this article incredibly helpful. I didn’t know Snowy but you certainly honor the friendship in your writing of him here! Love from your cousin Donna.